In this post I have explained some basic facts about DC to DC buck converters and also learn how to build a simple buck converter circuit. A buck converter is also popularly known as a step-down converter, since its basic function is to step down a higher input voltage level to a lower output voltage level, with high efficiency.

The practical buck converter circuit explained here uses only 3 transistors and is extremely easy to build. Even though the circuit is simple, it has a high efficiency.

The circuit can be used to drive 3.3 V LEDs from a higher input supplies such as from 12 V, or 9 V supply inputs.

The buck converter design can be also easily upgraded to operate higher rated loads instead of an LED.

Advantages of Buck Converters Compared to Linear Regulators

The main advantage of a DC to DC buck converter compared to a linear regulator is that buck converters are hugely efficient than linear regulators.

Linear regulators such as IC 7812, IC 7805, LM317, LM338 waste a lot of energy through heat dissipation, whereas heat dissipation in buck converters is minimal.

Due to minimal heat dissipation, a heatsink may not be required in buck converters, or this may be very small in size.

The efficiency of linear regulators may range between 25% and 50%, the efficiency of buck converters is mostly around 90%.

Basic Working of a Buck Converter Topology

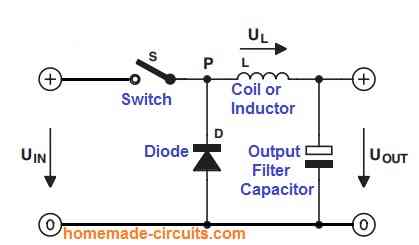

Referring to the figure below, let's try to understand how a 'buck' or a 'step-down' converter works. With a buck converter circuit, a higher input voltage can be transformed into a lower output voltage. Its basic mode of operation is described as follows.

As soon as switch S is pressed, a positive voltage develops across the inductor L. This is because UIN is higher than Uout. The coil initially tries to resist the instantaneous current flow. As a result, the current in the coil increases linearly, and energy begins storing in the coil.

Next, as soon as switch S is opened, the stored current flows through the coil into the output capacitor through diode D.

Since the voltage UL across the coil is now negative, the current through the coil reduces linearly. The output receives the energy that was captured and stored in the coil. Now, if Switch S is closed once again, the procedure begins afresh and keeps repeating as the switch is operated ON/OFF.

Modes of Operation

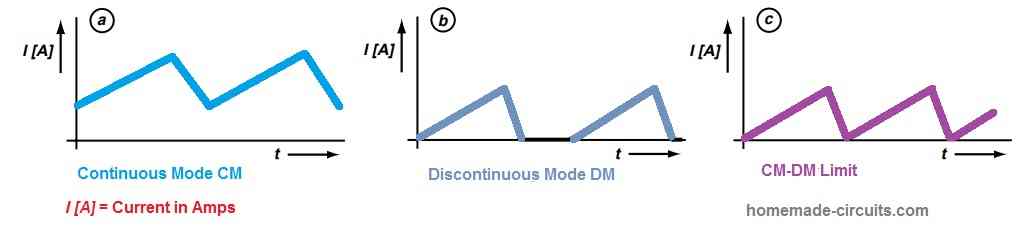

The voltage that appears at the output is determined by how the switch S is operated. According to figure below, there are three basic types of current flow.

- Referring to the figure (a) above suppose, the switch S is closed and opened such that the current flowing inside the coil isn't able to reach zero. In this situation a constant flow of current will be experienced through the coil. This is referred to as "continuous mode" (CM).

- Now let's imagine the switch S is closed and opened such that current is able to reach zero for part of the cycle, as illustrated in Figure (b). Then the circuit can be assumed to be operating in 'discontinuous mode' (DM).

- In the third scenario if suppose the switch is closed and opened such that the coil current is able to exactly reach zero as shown in figure (c), then we call this as CM/DM limit operation.

This means that, in a buck converter both the output voltage and power could be varied by adjusting the "on" periods of the switch. This is also called the mark-space ratio.

That's enough theory; now let's examine a straightforward real-world circuit.

Making a Practical Buck Converter Design

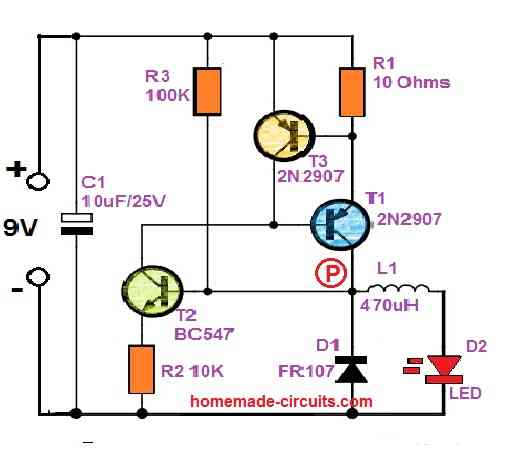

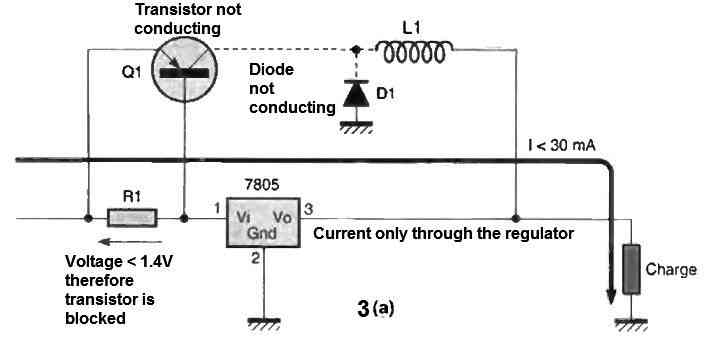

The following figure shows a simple practical DC to DC buck converter circuit using only 3 transistors and a few other passive elements.

It works in the following manner:

Switch S in this circuit is represented by transistor T1. The other components of the step-down converter are diode D1 and coil L1.

As soon as the circuit is powered, R3 supplies a base current to T2 (because D2's forward voltage spec is larger than 0.7 V) and T2 is switched ON.

With T2 conducting, T1 gets a base bias and it also begins conducting. In this situation, point P experiences an increase in voltage, which causes T2 to conduct even harder.

Now as point P's voltage reaches 9 V, the current through L1 starts to increase. The voltage across the coil and its inductance both influence how quickly the current inside it increases.

As the current across the coil increases, the voltage across R1 decreases. As soon as this potential hits 0.7 V (about 70 mA) causes T3 to turn ON. This quickly removes the base current of T1.

Since the current in L1 can now no longer increase, the voltage at point P starts to decrease. T2 as a result is switched off, followed by T1.

The current via L1 now travels via D1 until it drops to zero. This causes the voltage on T2 to increase again, and the process repeats afresh.

The transistors work as a thyristor with positive feedback, resulting in an oscillation. T3 makes sure that T1 is shut off at the predetermined current and that the circuit operates in CM/DM limit mode.

Upgrading the Circuit for Higher Loads

Instead of illuminating an LED, you could employ this circuit to operate a higher rated load. But with a higher load you will find the buck converter not oscillating.

This is due to the load preventing R3 from turning on T2 at startup.

This issue may be avoided by placing a capacitor (0.1uF) between point P and the base of T2.

Another smart move would be to smooth the voltage by connecting a 10 F electrolytic capacitor across the output.

The buck converter functions as a current source instead of a voltage source and is unregulated. However, for most straightforward applications, this will be more than sufficient.

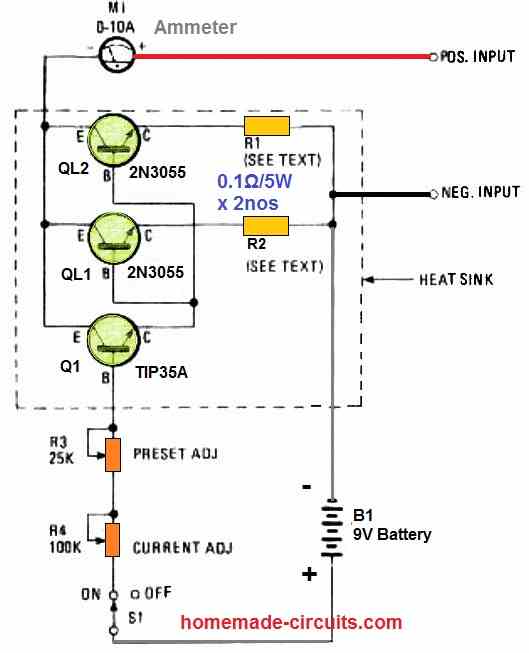

Simple Two Transistor Buck Converter Circuit

Parts List

- All resistors are 1/4 watt 5%

- R1 = 470 Ohms

- R2, R4 = 100 Ohms

- R3, R5 = 2.2 K

- Capacitors

- C1, C3 = 1000 uF/ 25 V

- C2 = 220 uF / 25 V

- Semiconductors

- D1 = FR107

- D2 = 12 V 1 watt Zener diode

- T1 = 2N2907

- T2 = BC547

- L1 = 120 uH

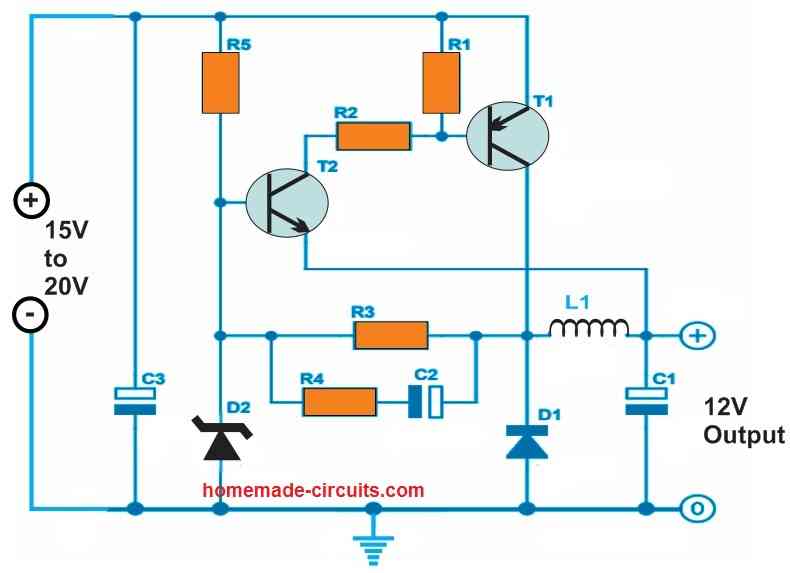

We can make the above design much simpler using just two transistors? Referring to the circuit diagram above, we can see a regulated step-down converter, which can generate 12 V DC from a 20 V DC. The main components of this design are transistor T1, diode D1 and coil L1.

The circuit works using the feedback between a combination of the PNP/NPN transistors. Here, the working of T1 is not dependent on the maximum coil current. Instead it is determined by the RC network of R4/C2.

The voltage regulation for this simple buck converter circuit is determined by the zener diode D2, associated with the emitter of T2.

This DC to DC buck converter design is highly efficient, which may be as high as 90%.

How to Build

- Step#1: Take 20 mm by 20 mm general purpose strip board.

- Spep#2: Clean the copper side with a sand paper.

- Step#3: Take the resistors and the diodes and bend their leads leaving 1 mm distance between their body and the leads.

- Step#4: Insert the resistors into the PCB and solder them. Cut the excess lead lengths.

- Step#5: Insert the transistors as per the same layout position as indicated in the schematic. Solder their leads, and trim the extended leads.

- Step#6: Now, insert the inductor, solder it, and trim its leads.

- Step#7: Finally insert, the capacitor and the LED, solder the leads. Cut the excess leads

Once the above assembly is done carefully interconnect the leads of the various components by referring to the schematic diagram. Do this using the pieces of the trimmed lead wires, previously cut.

If you are unable to connect the leads directly from the copper side, you can use jumper wire from the component side of the PCB.

How to Test

- Keep the LED disconnected at the start.

- Apply 9 V DC to the circuit.

- Measure the voltage across the points where the LED is supposed to be connected.

- It must be around 3 V to 4 V.

- This will confirm that you have build the buck converter correctly, and it is working correctly.

- You can switch OFF power and connect the LED back in its position.

- Now switch ON the DC again, you will find the LED illuminated brightly from the 9 V DC input with maximum efficiency.

How to Measure the Efficiency

To measure the efficiency you can connect an ammeter in series with the positive line of the 9 V DC.

Then you can multiply the current reading with the voltage (9 V).

The result could be somewhere around 20% higher than the watt specification of the LED.

This might prove an 80% efficiency for the buck converter circuit, and likewise.

Adjustable PWM Buck Converter Circuit

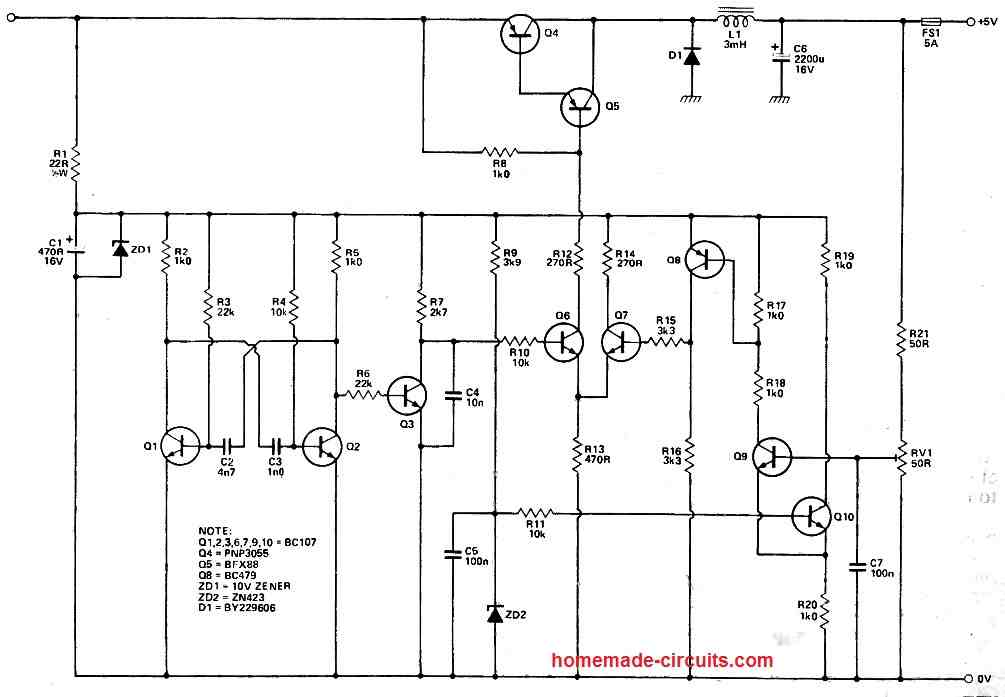

This circuit was initially designed with the purpose of generating a 5V power supply from a car battery to operate a BBC microcomputer.

Notably, the design refrains from employing integrated circuits (ICs), utilizing instead readily available discrete semiconductors salvaged from miscellaneous parts.

Efficiency Considerations

Achieving efficiencies surpassing 80%, this circuit outperforms linear regulators which generally exhibit maximum efficiencies ranging from 33% to 42%.

Astable Multivibrator and Pulse Generation

The operation commences with transistors Q1 and Q2 configured in an astable multivibrator arrangement.

This configuration yields a brief positive pulse at the base of Q3 at intervals of 50µs.

Consequently, the capacitor C4 discharges, subsequently recharging through the 2.7 kΩ resistor. This process delivers a gradually ascending voltage to the base of Q6.

Voltage Comparison and Regulation

Transistors Q9 and Q10 undertake a voltage comparison task, juxtaposing the reference voltage from the ZN423 with a segment of the regulator's output voltage.

This voltage slice derives from a potentiometer serving as the output voltage adjustment feature.

It's crucial to avoid substituting a zener diode for the ZN423, as the former's slope resistance reacts adversely to fluctuating battery voltages.

Adjustable Voltage Control and Pulse Width Modulation

As the potentiometer wiper voltage exceeds the reference voltage, Q8 activates.

Consequently, the ascending ramp at the base of Q6 must escalate to align with the voltage at the base of Q7.

This delay in activating the Darlington pair (Q4 and Q5) results in a narrower power output pulse to the choke.

This mechanism, known as pulse width modulation (PWM), in turn reduces the output voltage.

The nominal operating frequency is 20kHz, although it can vary considerably due to battery voltage fluctuations.

Output Stage and Energy Dissipation

The BY229-600 diode is specified for the catch diode, but in the prototype, a high-current rectifier proved effective.

The frequency of 20kHz seems manageable for these components.

Most wasted energy dissipates as heat in Q4, necessitating a suitable heat sink.

Output Voltage Feedback and Stability

The output voltage feedback attenuator incorporates 50Ω resistors to draw a minimum of 50mA from the output, essential for maintaining stability.

Alternatively, a 100Ω resistor could be shunted across the output, alongside a resistor and potentiometer (up to approximately 10kΩ each) to establish the correct feedback voltage.

When drawing 5A, a drop of 200mV in output voltage corresponds to an output resistance of 40 milliohms.

Grounding and Wiring

Designating the ground points with bold lines signifies their role as conduits for substantial currents.

These points necessitate robust connections, such as thick wiring or PCB tracks, tied back to a location proximate to the incoming battery's negative terminal.

This adherence to high-current grounding practices is a standard convention.

Output Regulation Strategies

The circuit does not currently encompass mechanisms for current limitation or crowbar protection.

Implementing a crowbar mechanism is straightforward, and current limiting can be achieved by manipulating Q9's base, thereby altering the power pulse's mark-space ratio.

Comments

You can add all the applicable protections explained in the following article, for Q1:

https://www.homemade-circuits.com/mosfet-protection-basics-explained-is/

only an RC snubber is needed across Q1…

When current is flowing through the primary coil of TR/1 and Q1 shuts off, it appears Q1 will be subject to very high voltage.

That voltage will be absorbed on the secondary side by the filter capacitor and the load…

Q1 is shown on the primary side. (The primary and secondary sides of a transformer have different phases.)

The energy stored inside the primary winding is thrown into the secondary winding which is then stored inside the filter capacitor. That is how a flyback system works. Q1 gets no high voltage, it only gets the Vinput voltage across it, for which it is rated appropriately.

There is no Vinput. The energy stored inside the primary winding is suddenly thrown into Q1 when Q1 attempts to turn off.

Add a snubber network across the primary.

How about putting a capacitor in series with the primary and connecting the combination to an h-bridge connected to vin & ground?

That would be an overkill, it is simply not required, the standard design is the best!

I prefer the cool and energy-efficient way.

There is no need for energy-wasting resistorized circuitry like snubbers if the transistors are turned on and off at the right times. Can you make up a design for that to input power into a 2-transformer application for me? (I don’t know how to turn 8 transistors on & off at the right times, just that it is possible but tricky without resistors/snubbers to do in a way that won’t burn anything and it doesn’t even require any heatsinks. I can detail my application a little more.)

Even I don’t know how to do that, that is why i prefer the standard design as explained in the above article.

You can’t figure a way to switch the transistors when their corresponding capacitors reach peak charge and current through their corresponding coils is ready to cross zero?

Can you draw your concept and let me see it, then maybe I can try figuring it out…

Thanks! I’ll do that.

Here:

https://www.homemade-circuits.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/H-bridge-with-series-capacitor.jpg

Why did you use two H-bridges and transformers?

I wanted both loads to be powered from the current source Vin. I don’t know the voltage of Vin, but I thought we might be able to calculate it and maybe the current from the specification of the model of the components T1-T8. I forgot an inlet capacitor, but power draw will be steadied some by the 1/4-wave offset too. It would also be nice if a driver for Vin could have a wide-range input or overvoltage protection without giving up much peak efficiency at substantial power draw or having much quiescent current. If not, or there was an unexpected delay between the cycling of the transformer-primary & capacitor pair timings, all of the h-bridge on the fast side could be temporarily turned off instead of immediately making the next step. The normal switching timing for bringing up the voltage should be: 1st T1 & T2 on with nothing else, next T1, T2, T3, & T4 on with the rest off, next T3, T4, T5, & T6 on with the rest off, next T5, T6, T7, & T8 on with the rest off, next T1, T2, T7, & T8 on with the rest off, and after all of that, it should repeat, each step made when the corresponding coil current is about to cross zero and the corresponding capacitor is at peak voltage.

I am finding it difficult to mentally simulate the entire setup, so I am unable to clearly understand the switching behavior of the design. It would be better if you could try testing it in some simulation software.

There are plenty of online free softwares which you can try…

Any spyware-free ones for Android?

Sorry, I have no idea about that.

At the time of each step, a capacitor’s charge is at a peak and the current through it, its transformer, and its H-bridge is 0. At this time, the H-bridge can reverse polarity to increase the later charge, by transferring power. That is what the cycle timings are for.

Please tell, what kind of PWM are you looking for and with what timing?

Not exactly PWM unless it’s feeding an inlet capacitor [through an inlet, iron-core high-current inductor, which could have a diode to ground]: the steps need to shut off the primary exactly when the energy is in the capacitor and the secondary coil and not in the primary coil. The back-on part of the steps could be delayed based on feedback/preset(s), but that would make some output noise. We could add a T9 between C1 and T1 and a T10 between C2 and T3, to reduce the noise, by filling-in for the H-bridges when an H-bridge is off, for an even number of steps. T9 and T10 would then supply TR1 and TR2 with only power already in C1 and C2, for more stability / clean output.

Let’s call an inlet transistor T0, an iron-core inductor L1, and inlet diode D0, for any future reference.

This will require a microcontroller or an Arduino operation, cannot be done with discrete components.

Can you write and specify what’s needed for RP2040 or RP2350 (generic versions of the Pico and Pico 2) microcontrollers? (I have an Uno, but I think it would be too slow.)

Can 1 or 2 0-6V 16-way MUX modules handle the task with 5-6 microcontroller pins (4 pins for a 4-bit address, and the pin(s) for input and output) while the microcontroller is also doing other things (e.g. running my 3D printer and/or more instances of my design)?

Can the microcontroller sleep when my loads are off / while voltage of stored energy remains adequate, or until a voltage or current could be about to be excessive (e.g. based on the fixed maximum possible increase over the latest value or last peak, perhaps via zener diode, capacitor with filter, optocoupler, etc. – discrete components)? (The sleep is intended to reduce quiescent power consumption. The voltage or current fixed at Vin by modulating T0, as we discussed earlier, by discrete components with regular PWM (or with PFM), fixes or limits some aspects/properties of everything downstream in the circuit and thereby allows the microcontroller to be able to sleep if coded and wired for it.)

That looks difficult, because I can only create basic Arduino codes not complex ones like this…

If it’s just a matter of getting the value from a mathematical formula you have into a variable, then, regardless of how complicated it is, if you send/post the formula, which other variables have which inputs, and which language, I can readily make a try at a statement, which try we could debug together in case it had error(s).

That 1st step is not part of the repetitive cycle.

No, there is no conductive path from the primary winding through the secondary coil.

You are right, so you can add a calculated snubber network across the primary winding.

Please read this article:

https://www.homemade-circuits.com/do-we-need-a-freewheeling-diode-across-the-inductor-in-boost-converter/

I don’t know about that, you will need to find it by checking datasheets.

What is the greatest voltage that can be converted without inefficient SiC transistors? (I’m interested in using the most efficient type of isolated power conversion.)

When you are already limiting the input current, then no such protections are required…

Are those or something needed to shut down the oscillator when it is about to cause overcurrent? How do we set up the minimum overcurrent protection?

Thanks!

If I put a heatsink on Q1, the input is 24V, and TR/1 is adequate, how much input current should I allow to prevent burning?

In that case, you can try the following tool, and apply it with my earlier 555 flyback circuit:

https://www.homemade-circuits.com/smps-calculator-using-toroidal-ferrite-transformer/

I wanted something of the same type of power conversion transformer/core and approximate number of turns as the S0230b5723c7e401f98d6d9af240b5789F.jpg I indicated earlier, with similar ampacity (e.g. 3A or 5A), including the relatively high efficiency available for this technology, as well as the isolation [which you suggested a 4-pin optocoupler could help provide], but I don’t want all of the automatic features built-in and I don’t know how to design it myself, so I’m asking for your help. I don’t need it to buck and would like an equal or, if not equal, higher, output voltage than input voltage without straying too far from the input voltage when the input voltage is close to the fixed value, but I’m interested in controlling it with the 24V zener and, although I didn’t exactly mention it earlier, it would be best if it normally kept its voltage up near that [as we discussed] with the zener, but preferably without maintaining output voltage when the current would otherwise overload the transistor, and if it had a low quiescent current. The input voltage will be limited to the 24V [or another fixed value] except at high input current draw, when it would help to lower output voltage to prevent overload. Short windings of big-diameter wire on TR/1 will prevent overload of TR/1, as well as reducing ohmic losses.

Sure, you can draw your own version and send it to me…

The open-circuit voltage doesn’t seem like a very practical overall design figure to me. I want to power loads that draw current.

Note: This calculator is focused on giving basic SMPS design values like inductor size, frequency, number of turns, and output voltage. It does not include full electrical stress analysis like input RMS current, switch peak current, or efficiency estimation. For that you can use simulation tools like LTspice or detailed datasheet formulas.

For your low current application you can use your input current limiting method. I basically meant to say that input current is immaterial, it will have no impact on the circuit, unless and until the load specification is wrongly selected.

The calculator doesn’t take load current and doesn’t give input current (peak nor RMS).

Limiting input current with fixed voltage limits wattage (both in & out) and therefore output current.

You will have to calculate TR/1 using the following calculator:

https://www.homemade-circuits.com/smps-flyback-boost-converter-calculator/

Input current is not important, it can have any value. It is the load current that matters cannot exceed the MOSFET Q1 rating, and the transformer wire rating.

You just have to remove the R4, VR1 and put a 24V zener 1W diode between the positive rail and R5, cathode of the zener diode going to the positive rail, and anode to the R5, then connect the optocoupler’s LED anode with the zener/R5 junction. R5 can be a 2.2k resistor.

Can you make a diagram / specify values?